Predicting Life Expectancy

Intro

The focus here is on EDA (Exploratory Data Analysis) and investigating the best choice for the \(\lambda\) hyperparameter for LASSO and Ridge Regression.

We will be working on the Life Expectancy CSV data obtained from WHO.

Peeking at Data

We begin by viewing the columns of the Life Expectancy Dataframe:

import seaborn as sns

import pandas as pd

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

pd.options.display.float_format = '{:.2f}'.format

le_df = pd.read_csv("life_expectancy.csv")

le_df.columns

Index(['Country', 'Year', 'Status', 'Life expectancy ', 'Adult Mortality',

'infant deaths', 'Alcohol', 'percentage expenditure', 'Hepatitis B',

'Measles ', ' BMI ', 'under-five deaths ', 'Polio', 'Total expenditure',

'Diphtheria ', ' HIV/AIDS', 'GDP', 'Population',

' thinness 1-19 years', ' thinness 5-9 years',

'Income composition of resources', 'Schooling'],

dtype='object')

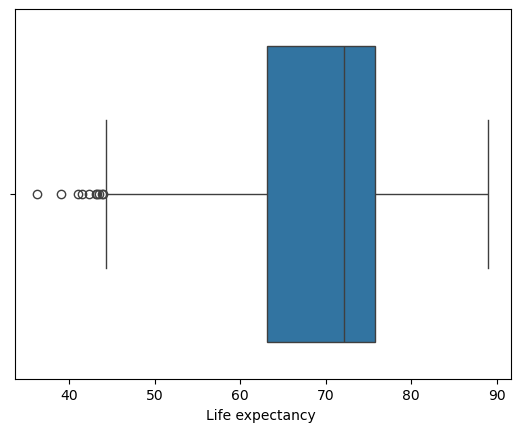

We can then view the range of our life expectancy values with a box plot:

sns.boxplot(x=le_df['Life expectancy '])

plt.show()

From here we can glean

- the folks that died early at late 30's, early 40's;

- the minimum and maximum excluding these outliers (whiskers)

- the first and third Quartiles; and

- the mean (\(\mu\)) life expectancy

le_df.info()<class 'pandas.core.frame.DataFrame'> RangeIndex: 2938 entries, 0 to 2937 Data columns (total 22 columns): # Column Non-Null Count Dtype --- ------ -------------- ----- 0 Country 2938 non-null object 1 Year 2938 non-null int64 2 Status 2938 non-null object 3 Life expectancy 2928 non-null float64 4 Adult Mortality 2928 non-null float64 5 infant deaths 2938 non-null int64 6 Alcohol 2744 non-null float64 7 percentage expenditure 2938 non-null float64 8 Hepatitis B 2385 non-null float64 9 Measles 2938 non-null int64 10 BMI 2904 non-null float64 11 under-five deaths 2938 non-null int64 12 Polio 2919 non-null float64 13 Total expenditure 2712 non-null float64 14 Diphtheria 2919 non-null float64 15 HIV/AIDS 2938 non-null float64 16 GDP 2490 non-null float64 17 Population 2286 non-null float64 18 thinness 1-19 years 2904 non-null float64 19 thinness 5-9 years 2904 non-null float64 20 Income composition of resources 2771 non-null float64 21 Schooling 2775 non-null float64 dtypes: float64(16), int64(4), object(2) memory usage: 505.1+ KB

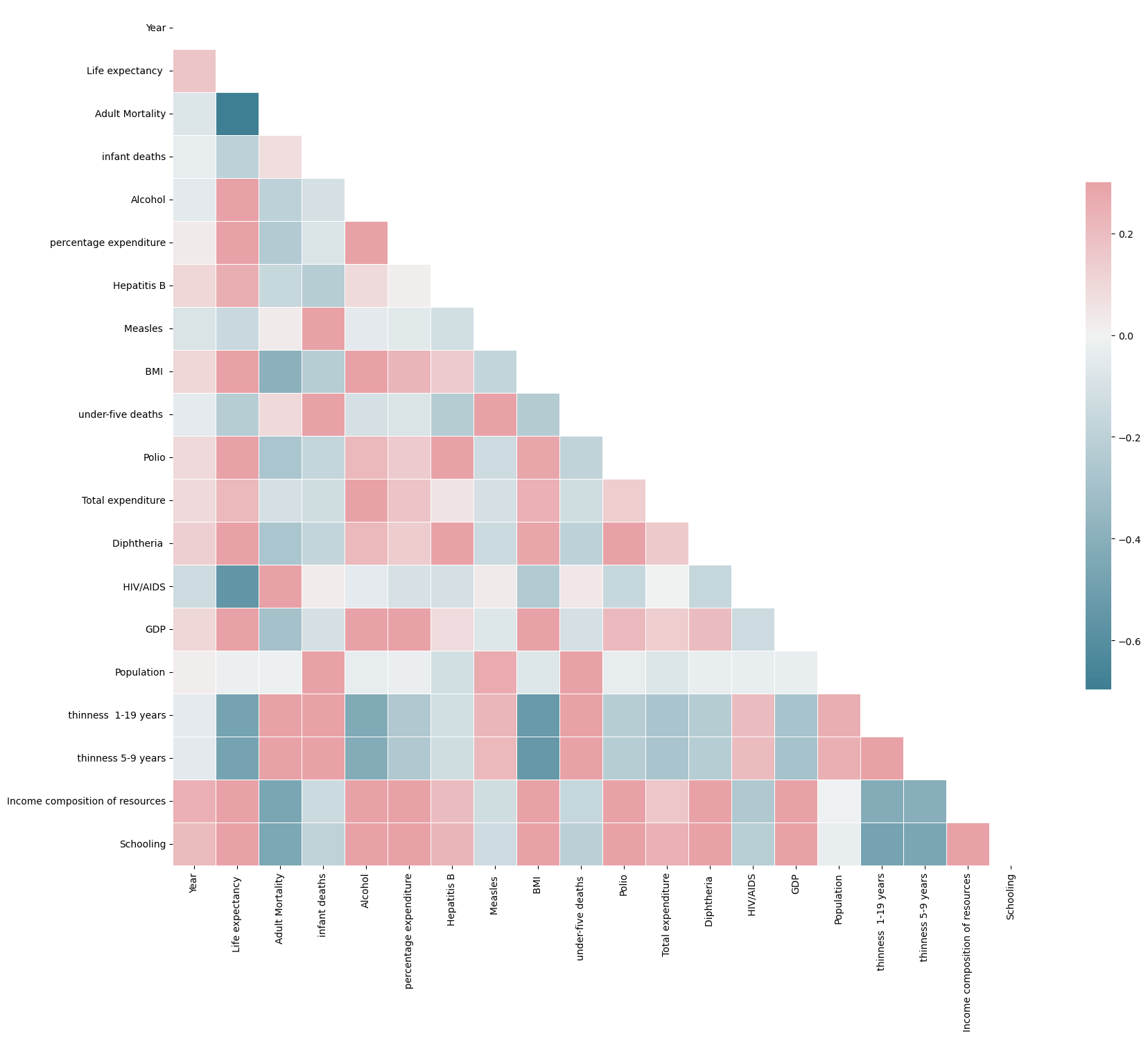

Correlations

Then to produce a correlation matrix we would require exclusively continuous values. As such I have dropped those that are not:

le_df = le_df.drop(columns=['Country','Status']) import numpy as np

corr_mat = le_df.corr()

mask = np.zeros_like(corr_mat, dtype=bool)

mask[np.triu_indices_from(mask)] = True

f, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(20,19))

cmap=sns.diverging_palette(220,10, as_cmap=True)

sns.heatmap(corr_mat, mask=mask, cmap=cmap, vmax=.3, center=0,

square=True, linewidths=.5, cbar_kws={"shrink": .5})

plt.show()Note: We only need to view the lower / upper triangular section of the matrix due to the symmetry.

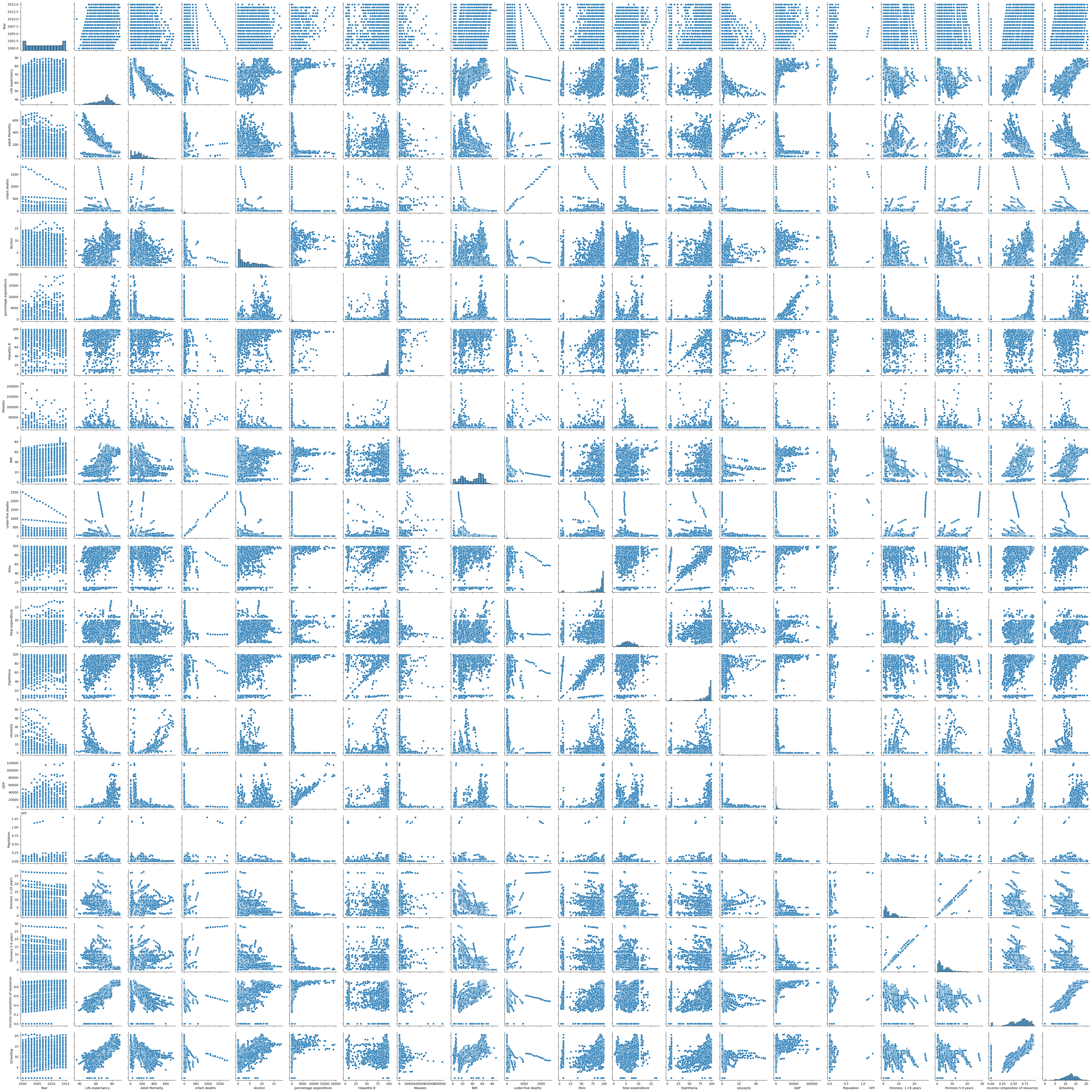

Letting our libraries continue doing the heavy lifting for us:

sns.pairplot(le_df)

plt.show()

From here we learn that Adult Mortality is very negatively correlated with Life Expectancy (which makes sense). Also the 3 most positively correlated features with Life Expectancy are

- HIV/AIDS 0.753

- Income Comp of Resources 0.729

- Schooling 0.722

All of which are interesting in their own right.

Standard Scaling

Because we will be using regularised regression today and the penalties on weight will be affected by the magnitudes of the features we must first standardise our data:

from sklearn.preprocessing import StandardScaler

le_df_noNAN = le_df.dropna()

X = le_df_noNAN.drop(columns=["Life expectancy "])

y = le_df_noNAN["Life expectancy "].copy()

scaler = StandardScaler().fit(X)

scaled_X = scaler.transform(X)

print(f"Feature Means: {scaled_X.mean(axis=0)}")

print(f"Feature Variances: {scaled_X.var(axis=0)}")Feature Means: [-7.96290464e-15 -7.75607595e-17 -4.30893108e-18 6.89428973e-17 2.58535865e-17 1.63739381e-16 -4.30893108e-18 -6.89428973e-17 -2.58535865e-17 2.57458632e-16 1.68048312e-16 1.29267933e-17 6.03250352e-17 8.61786217e-17 -3.01625176e-17 5.60161041e-17 -7.75607595e-17 1.72357243e-16 7.92843319e-16] Feature Variances: [1. 1. 1. 1. 1. 1. 1. 1. 1. 1. 1. 1. 1. 1. 1. 1. 1. 1. 1.]

Splitting Training and Test Data

Now we split the testing and training data

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

X_train, X_test = train_test_split(X, test_size=0.2, random_state=73)

y_train, y_test = train_test_split(y, test_size=0.2, random_state=73)Empiricism on Lambda (Ridge)

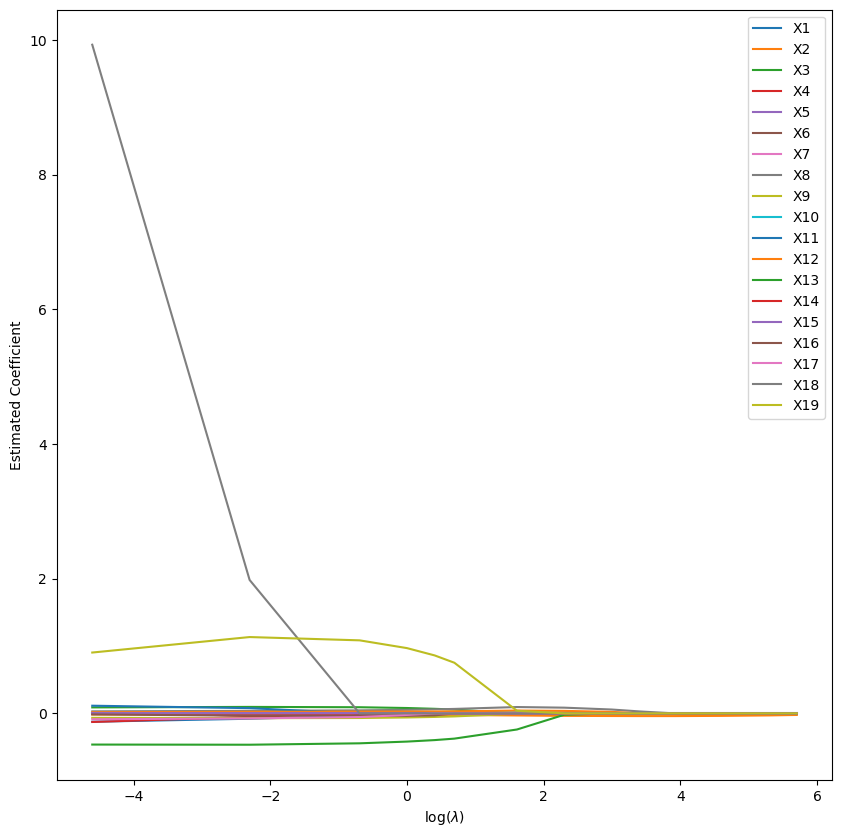

And start training a Ridge regression with varying values of the hyperparameter lambda:

%%time

import warnings

warnings.filterwarnings("ignore")

from sklearn.linear_model import Ridge

lambdas = [0.01, 0.1, 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 5, 10, 20, 30, 50, 100, 200, 300]

N = len(lambdas)

coefs_mat = np.zeros((X_train.shape[1], N))

for i in range(N):

L = lambdas[i]

ridge_lm = Ridge(alpha=L).fit(X_train, y_train)

coefs_mat[:,i] = ridge_lm.coef_

plt.figure(figsize=(10,10))

for i in range(X_train.shape[1]):

lab = "X" + str(i + 1)

plt.plot(np.log(lambdas), coefs_mat[i], label=lab)

plt.legend()

plt.xlabel(r"log($\lambda$)")

plt.ylabel("Estimated Coefficient")

plt.show()

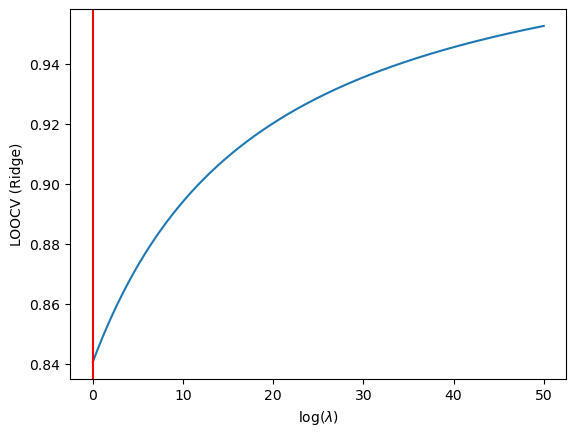

We then find the best Lambda:

%%time

lambdas = np.arange(0,50.1,step=0.1)

n = X_train.shape[0]

N = lambdas.shape[0]

CV_score = np.zeros(N)

curIdx = 0

#X_train = X_train.to_numpy()

#y_train = y_train.to_numpy()

for L in lambdas:

sq_errs = 0.

for i in range(100):

x_i = X_train[i]

x_removed_i = np.delete(X_train, i, axis=0)

y_i = y_train[i]

y_removed_i = np.delete(y_train, i, axis=0)

mod = Ridge(alpha=L).fit(x_removed_i, y_removed_i)

sq_errs += (mod.predict(x_i.reshape(1,-1))-y_i)**2

CV_score[curIdx] = sq_errs/n

curIdx += 1

min_idx = np.argmin(CV_score)

plt.plot(lambdas, CV_score)

plt.xlabel(r"log($\lambda$)")

plt.ylabel("LOOCV (Ridge)")

plt.axvline(x=lambdas[min_idx], color='red')

plt.annotate(f"$\lambda = {lambdas[min_idx]}$", xy=(25,1800))

plt.show()

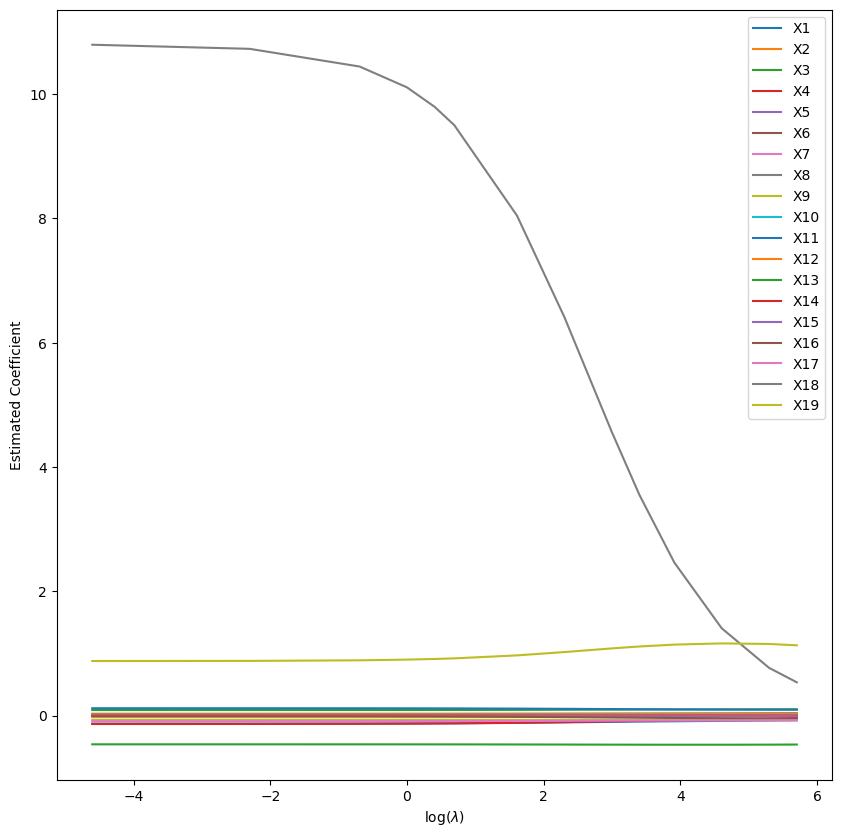

Empiricism on Lambda (LASSO)

We then repeat for our L1 regularisation model:

from sklearn.linear_model import Lasso

lambdas = [0.01, 0.1, 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 5, 10, 20, 30, 50, 100, 200, 300]

N = len(lambdas)

coefs_mat = np.zeros((X_train.shape[1], N))

for i in range(N):

L = lambdas[i]

ridge_lm = Lasso(alpha=L).fit(X_train, y_train)

coefs_mat[:,i] = ridge_lm.coef_

plt.figure(figsize=(10,10))

for i in range(X_train.shape[1]):

lab = "X" + str(i + 1)

plt.plot(np.log(lambdas), coefs_mat[i], label=lab)

plt.legend()

plt.xlabel(r"log($\lambda$)")

plt.ylabel("Estimated Coefficient")

plt.show()

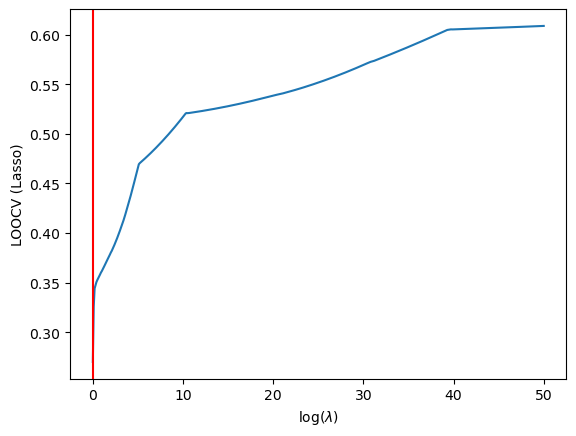

Thus we find the optimal lambda to be…

%%time

lambdas = np.arange(0,50.1,step=0.1)

n = X_train.shape[0]

N = lambdas.shape[0]

CV_score = np.zeros(N)

curIdx = 0

#X_train = X_train.to_numpy()

#y_train = y_train.to_numpy()

for L in lambdas:

sq_errs = 0.

for i in range(20): #note we are not going to N

x_i = X_train[i]

x_removed_i = np.delete(X_train, i, axis=0)

y_i = y_train[i]

y_removed_i = np.delete(y_train, i, axis=0)

mod = Lasso(alpha=L).fit(x_removed_i, y_removed_i)

sq_errs += (mod.predict(x_i.reshape(1,-1))-y_i)**2

CV_score[curIdx] = sq_errs/n

curIdx += 1

min_idx = np.argmin(CV_score)

plt.plot(lambdas, CV_score)

plt.xlabel(r"log($\lambda$)")

plt.ylabel("LOOCV (Lasso)")

plt.axvline(x=lambdas[min_idx], color='red')

plt.annotate(f"$\lambda = {lambdas[min_idx]}$", xy=(25,1800))

plt.show()

Results

It seems that in both situations we have fucked up. The LASSO and Ridge hyperparameters are being found to be 0. A quick fitting of the traning data to sklearn's LassoCV model may help clear some confusion:

from sklearn.linear_model import LassoCV

from sklearn.metrics import mean_squared_error

m_lassoCV = LassoCV(cv=5).fit(X_train, y_train)

ypred_train_lassoCV = m_lassoCV.predict(X_train)

ypred_test_lassoCV = m_lassoCV.predict(X_test)

print(f"Mean Squared Error (TRAIN): {mean_squared_error(y_train,ypred_train_lassoCV)}")

print(f"Mean Squared Error (TEST) : {mean_squared_error(y_test, ypred_test_lassoCV)}")

print(f"With Lambda as {m_lassoCV.get_params()}")

Mean Squared Error (TRAIN): 62.824553484016874

Mean Squared Error (TEST) : 68.37568737602082

With Lambda as {'alphas': None, 'copy_X': True, 'cv': 5, 'eps': 0.001, 'fit_intercept': True, 'max_iter': 1000, 'n_alphas': 100, 'n_jobs': None, 'positive': False, 'precompute': 'auto', 'random_state': None, 'selection': 'cyclic', 'tol': 0.0001, 'verbose': False}

Conclusion

The above shows that our analysis was not incorrect in attempting to determine the most optimal \(\lambda\)s, but rather a mistake has occurred in the preprocessing step causing the statistical signifance of my data to become muddled. In a later refactoring I may come back and improve my preprocessing, or abandon it completely in favour of a more homogenous dataset.

from sklearn.metrics import r2_score

print(f'Train Accuracy: {r2_score(ypred_train_lassoCV, y_train)}')

print(f'Test Accuracy: {r2_score(ypred_test_lassoCV, y_test)}')Train Accuracy: -8.965044425866656 Test Accuracy: -7.17445447809699